The Compassionate Use of Force

I have been thinking a lot lately about the aspect of compassion in our daily lives, it’s a benefit to ourselves as individuals, and also the benefit of compassion as a greater good to the greater world community.

The problem that I have been analysing and contemplating is how compassion fits in with those of us who teach and use physical force for the protection of others and ourselves.

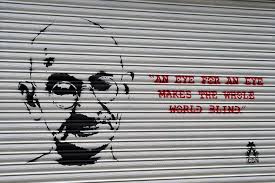

The general perception of compassion that most people have would be linked to a passive and non-violent action (such as Mahatma Gandhi and Martin Luther King Jr).

My Question is, Can The Use of Force Ever Be Considered An Act of Compassion?

For example, if someone was physically assaulting another person could another person use physical force to stop them, and if so, could this be seen as an act of compassion?

From my own personal perspective, there has to be an active element of compassion.

Otherwise, I feel that we would be far from compassionate by standing back and letting someone become harmed if we had the capability and means to stop it.

Yet how does this fit with the bigger view of compassion?

For example, the Buddhists (who are the Olympic athletes of compassion), sometimes are possibly seen to be using compassion in a fairly passive way, if for example, we consider the Chinese domination of Tibet.

Being Compassionate When Being Imprisoned and Tortured

In this situation, many Buddhist monks who have suffered extreme hardship in Chinese prisons have not actively resisted or fought back when they have suffered torture at the hands of their captors.

They instead focussed their minds single-pointedly on compassion.

In one interview recalled by the Dalai Lama, he talks openly about how he once had the opportunity to speak to a Buddhist Monk who had spent many years in a Chinese prison.

During the conversation the monk was asked by the Dalai Lama if he was ever scared, to which his reply was:

“Yes. I was scared of losing my compassion towards the Chinese”.

Now, this is a remarkable feat of compassion, but does this ideal of Buddhist compassion have any bearing in the average person’s day-to-day life, especially those of us who are not Buddhists?

Interestingly the then Prince Charles (now King Charles) had spoken about the need for NHS staff to be more compassionate.

He has called for a service that accounts for “the core human elements of mind, body and spirit” as well as disease and he urged medical professionals to develop a “healing empathy” to help patients find their own path to health.

The NHS has also issued a ‘Quality statement’ stating that:

“Patients are treated with dignity, kindness, compassion, courtesy, respect, understanding and honesty”.

Is It Reasonable To Consider That Staff Should Be More Compassionate?

With regard to the NHS, it is of course reasonable to consider that people, especially patients, should be treated with compassion.

That makes logical thinking as they are probably suffering already.

But there’s a fundamental problem.

How To Become More Compassionate?

How do we teach staff to become more compassionate?

This is something that requires training in.

Staff need to be taught how to generate compassionate states and thus become more compassionate.

It isn’t something that you ‘just do’. It needs cultivating.

I’ve just read one document produced by the NHS.

In it the word ‘compassion’ is mentioned 167 times and the word ‘compassionate’ mentioned 44 times.

The problem however, is that no where in the document does it talk about how to generate compassion.

But What About Someone Committing An Act of Violence?

How do we apply compassion to that type of situation?

In his new book ‘The Good Heart’ the Dalai Lama states that:

“It is definitely the case that there is an active element to compassion, and the possibility is open to the use of force, if it is deemed really necessary”.

The Ferryman Was a Murderer

In explaining this from a Buddhist perspective he tells the story of the Buddha, who (in a previous life as a merchant) when on a ferry crossing a river, found himself in a difficult situation.

It transpired that the ferryman was a murderer and was planning to kill all 499 passengers in the night on the ferry.

There was no other way that the Buddha could deal with the situation other than getting rid of the murderer.

The Buddha took the responsibility on himself to do that and in doing so not only saved the lives of 499 people, but he also saved the murderer from facing the negative consequences of killing so many people.

From a Buddhist perspective, the sacrifice was to take upon himself the negative act of killing a person and to face the consequences of that act.

This was an act of compassion.

The Dalai Lama Goes On To State…..

The Dalai Lama does go onto state that it is always better to avoid a situation that would require violent means, and this exactly the same principle of what good risk management in our civilised society requires today – the elimination or reduction of the risk of engaging in a violent act.

However, he goes on to say:

“Nevertheless, if you find yourself in a situation in which you must clearly act in a forceful way in defence, then you must make the appropriate response.

In this context, it is important to understand that tolerance and patience do not imply submission or giving in to injustice.

Tolerance, in the true meaning of the word, becomes a deliberate response on your part to a situation that would normally give rise to a strong negative emotional response, like anger or hatred.

This can be seen in the Tibetan term for patience, soap, which literally means “able to withstand”.

This is especially the case with the tolerance of being indifferent to harms that are inflicted upon one”,

and this is what I was referring to earlier in relation to the story about the monk in prison.

The Dalai Lama also goes on to say:

“One might misinterpret this to mean that we should give in or submit ourselves to whatever harm someone else might inflict on us – one might think it means that we should just say, “Go right ahead and hurt me!”

But this is not what this kind of tolerance is.

Rather it is a courageous state of mind that prevents us from being adversely affected by that incident; it helps to keep us from experiencing mental suffering when we encounter harm. It does not mean that we just give up.”

In short, what the Dalai Lama is conveying is that acting forcefully, even to the point of taking a life, can be seen as compassionate, provided that it is not motivated by anger or hatred.

This is also true of the basic principles of law in relation to the use of reasonable force too.

Conflict Management, Equality & Diversity and Equal Opportunity Training

Today we have staff sent on ‘conflict management’, ‘equality and diversity’ and ‘equal opportunity’ courses all designed to help them monitor and regulate their own behaviour when faced with difficult situations or people of a different ethical or cultural background.

In many self-defence and use of force courses techniques are taught within a context of defending against a violent or aggressive individual.

So in all cases, the person on whom our attention is focused on is seen as a being separate to us and separation causes differences to arise.

Restraint Reduction and Restraint Elimination

There are also a number of initiatives towards ‘restraint reduction’ and even ‘restraint elimination’ but the aspect of wanting to reduce or eliminate restraint will ensure that restraint is here to stay.

In short, what you resist persists!

For example, you can’t have a right without a left.

If no ‘left’ existed the ‘right’ would also not exist because everything exists in co-existence.

In the same way you can’t have an ‘above’ without a ‘below’ for the same reasons.

So when I hear people talking about ‘restraint reduction’ and ‘restraint elimination’ the very fact that they want to reduce it or eliminate it results in giving more energy to its existence.

This is the very same reason as to why Mother Teresa would never go to a ‘anti-war rally’.

And interestingly, in nearly every recent restraint related exposé, including abusive staff behaviour and even deaths in restraint, outside of the police and the prison service, the organisations (and in some cases the training providers) had signed up to some for of restraint reduction scheme.

All People Are The Same. We Are All Connected

The Buddhist context however, is to see all people as if we are all the same, because everything is connected to everything else. This is called ‘interbeing’ and I’ve written other blog posts and recorded videos about that if you want to learn more about that.

This sameness makes it easier for compassion to come to the fore, and, in my opinion, it would be more valuable and more sustainable than simply sending staff on courses to ‘learn’ a few ‘skills’ to ‘manage’ other people who by the focus on ‘behaviour management’ will be seen as different as opposed to the same.

Compassion can also be cultivated or increased by certain meditative and mindfulness practices, and let’s face it, the Buddhists are the ‘Olympic Champions’ at these practices so there is a lot we can learn from them.

I’ve been practicing meditation and mindfulness for many years now. It has helped me become a more compassionate and considerate human being and has allowed me to build ‘pauses’ into my thinking (an important thing when having to deal with any form of conflict).

So now, instead of merely reacting to something, I now have the ability to stop, consider my response and decide what the best response option is.

Learning how to cultivate compassion has enabled me to create a ‘pause’ button if you like.

If you’d like to consider an evidence-based approach to helping your staff become more compassionate, which will also benefit your staff’s health and well-being and possibly even reduce sickness, absenteeism, reduce costs and increase productivity, drop me an email at [email protected].

Have a great day.

Other Related Blog Posts

Stress Costs UK Employers Up To 56 Billion Pounds A Year

The Cost of Stress and Mental Health in The UK (Video)

Stress and Mental Health Pandemic

How a Change In Lifestyle Changed People’s Genes (Video)

How The Body Goes Into Famine Mode When In Stress (Video)

Why You Mustn’t Do Fear, Stress or Live in a State of Lack (Video)

Why Stress Management and Mental Health First Aid Training Doesn’t Work (Video)

there is also the element that certain people in certain walks of life can confuse compassion for weakness and then take advantage of that.

moreover in an act of violence is it better to restrain an individual that is trying to cause harm rather than to cause a violent act in defense.

So I do believe that there is a compassionate use of force. For even the monks would use force to stop the taking of a life.

Mark as you are aware I have used all shorts of force over the years and looking back I can see that must of it was to help others so could be considered Compassionate. Your words has put this very much into focus for me and will help me going forward, both personally and as a teacher.

regards Andrew.

Can and force be used as an act of compassion?

Absolutely, from my perspective (Law Enforcement) we act with compassion when using force where individuals are a suffering mental health crisis or where they are so impaired they are incapable of caring for their self in a sufficient manner. This use of force is primary aimed to protect the individual, in a dignified and compassionate manner, and less aimed at the enforcement issues.

I would argue, that this is not the sole domain of the Police, but also anyone who acts to protect another person, where they are incapable for whatever reason.

I would pose the question: When a Teacher acts to protect a student (aggressor) by stopping a violent confrontation, are they not acting with some compassion for that child, given the fact that by their very nature, children are not fully aware of the consequences of their actions (In the socially accepted behaviour concept)?

I think the US military did some testing a few years back and discovered that tapping into human compassion for others (fellow soldiers, civilians you are protecting etc) was the route to empowering soldiers to accept the violent actions they would take against the ‘perpetrators’. Previous attempts to encourage fearlessness, numbness or ‘de-humanisation’ of others failed to strike a chord with intrinsic human nature (except in the case of sociopaths).

Very interesting and an aspect that I hadnt thought of in that way before.

Fantastic read

Thank you for posting this Mark. I agree that use of force can, and perhaps always could come from a compassionate place within us? If it comes from a place of vengeance or hostility, maybe we risk escalating a violent situation. I wrote this, its deliberately ‘out on a limb’, something for our staff to debate/aspire to in our Behaviours that Challenge training:

“The angry person expends energy struggling and does no harm. The angry person is held by these two people, physically and emotionally. We can talk to them, telling them they are safe and that we will help. We are confident in our approach, solely focused on protecting the threatened person, making our strong, blame-free physical presence known to the angry person, until that person has exhausted their anger and/or becomes calm by containing it for themselves”

Interesting read Mark,I used to be a Health care assistant on LD and Mental Health wards,I’m now a PMVA instructor for an NHS trust,so I found your article very topicle in light of seni’s law and resent media coverage of mental health care.

Thank you for posting your thoughts on this subject Mark. As you know, my team are required to have the skills to physically intervene when it is necessary to protect my son who is a 6′ 2″, physically strong young man with Autism. He suffers with severe anxiety and an inability to communicate effectively, so his aggressive actions always come from a place of fear.

I have found that the most successful team members are those who not recognise when it is necessary to physically intervene, but do so from a position of true empathy. This enables them to put themselves in my son’s place and truly understand why he reacts in the way he does in certain situations. Not only does this mean that they are usually “ahead of the game” and can foresee difficulties before a crisis is reached, but they are acting in a way that my son finds reassuring. In addition, their obvious compassion is communicated to onlookers who are then able to have confidence that what they are seeing is ok, which also adds to the safety aspect of the intervention when in public.

Perhaps even more importantly, the compassionate basis from which the physical intervention comes, allows team members to reconcile the experience of what could be a traumatic event, with their desire to support and care for my son. Another way of describing what we do is perhaps the phrase “tough love” because we all understand that without the skills that you Mark have taught us, my son’s life would be very different, and everyone, including him, would be too scared to take him out into the community. Together, we have enabled him to continue to be an active member of his community and to enjoy the freedom of simple things like going to the park or to the local leisure centre. This is truly what I would call compassionate intervention, and I will be forever grateful for what you have taught us.

Hi Helen, thank you for your comments and the points you raise are very valid as I obviously know you and your family very well and I have the utmost respect for what you all do in supporting your son.